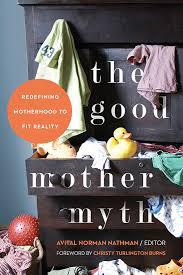

The ‘Good Mother’ myth is alive and kicking. So says an important new collection of essays, edited by Avital Norman Nathman and designed to paint a rather messier picture of motherhood indeed. Nathman and Co are not alone in this endeavor. There is now an entire industry dedicated to debunking the fantasy of the Good Mother by chronicling the missteps and misjudgements of her naughty stepsister, the Bad Mother. It is a mass movement particularly prevalent in the blogosphere and its worthy cause of telling it like it is can be traced back to Ayelet Waldman’s genre-defining book of that name.

As both Nathman and Waldman have pointed out, the Good Mother is largely a chimera. Like the boggart from Harry Potter, she is a shape-shifter who takes the form of her intended victim’s worst fear. If you can’t cook, the Good Mother is the one who fills her children to the brim with homemade, organically-sourced super food. If you plop your kids in front of the TV, the Good Mother is the one who lets them play only with wooden toys, whittled by elves in the recesses of the Swiss Alps. If you work full time, the Good Mother is the one showing up for every single school event. If you bottle feed, the Good Mother is a lactating goddess, dripping with liquid gold.

The Good Mother is often our inner voice talking back to us. She is a kind of Jiminy Cricket, who sits on our shoulders, shining a light on the things we might like to have done differently or on the things we might like to be doing better. The opposite of the Good Mother in this regard is not the Bad Mother: it is the Real Mother. Parenting is damn hard work. Most of us fail to live up to our own expectations. The interesting question is not about what those expectations are; it is about why we berate ourselves for not meeting them in the face of reality. A potential answer - and this is the one The Good Mother Myth focuses on - is because we feel confronted, at every turn, by women who seem to be getting it ‘right.’

With the proliferation of venues in which she can haunt us, from the media to Facebook to Pinterest, the Good Mother is everywhere these days. And yet, the backlash against her has been equally fierce. One only has to peruse wildly popular websites like Scary Mommy to see the extent of this effort. But how many essays about the shit hitting the fan, literally and metaphorically, need to be published before we can extricate ourselves from the Good Mother’s impeccably manicured grip? My guess is that there is no number high enough, that the Good Mother will never vanish from the collective consciousness, because the various parts of her will continue to manifest themselves in actual women, who are telling their stories. And what’s more: I’m not sure she should disappear wholly. Her dogged persistence leads me to believe she serves some kind of philosophical purpose.

When it comes to mothering, there are aspects most of us would consider highly subjective and irrelevant to the welfare of the child: what kind of stroller you buy, for instance. So too there are aspects that most of us would consider either objectively wrong (abuse, neglect) or objectively undesirable (the baby rolling off the bed, screaming at the toddler all day long). Then there is the murky middle ground, the moral carcass around which the vultures of the Mommy Wars circle. This is where the subjective and the objective become disconcertingly blurred and this is where the Good Mother’s voice blares the loudest, though she does not utter the same words to each of us (my Good Mother, for instance, does not craft or co-sleep).

Navigating the emotional minefield of this middle ground is of notable difficulty for today’s crop of mothers. We are a generation that invests more in our children than ever before and we have reams of information at our fingertips about how ‘best’ to do it. Each decision we make - from whether we stay home with them to when we wean them to how much we praise them - takes on a disproportionate, almost mystical, quality. As a result, we have become overwhelmed by what is subjective about parenting and extra sensitive to perceived criticism about what is more objective. As Fionola Meredith has articulated recently vis-à-vis breastfeeding, ‘[modern] mothers…will simply not tolerate anybody making them feel bad.’

If the Good Mother makes us feel bad, however, it is because we let her. She is not the problem by herself. The problem is that we have allowed her to become a vehicle for envy and guilt and self-flagellation, instead of a means of identifying what matters most to us and a force for mindful improvement therein. The fear of getting it ‘wrong’ has led us down a slippery slope, where we take comfort in being told everything we do is ‘right’. But everything we do as parents will not yield the perfect outcome, even by our own standards. That’s okay. We shouldn’t be holding the Good Mother up as a mirror in this respect, reflecting our failures back to us. We should be holding her in our heads as an ideal, an incentive to become the best version of the Real Mothers we actually are.

This post is part of the Brilliant Book Club. Check out these interesting takes on The Good Mother Myth at the links below:

- (Left Brain Buddha) Remember When You Said You’d Never Have Kids?

- (Mommy, For Real) Dispelling Myths and Reinventing Motherhood

- (School of Smock) Challenging the Good Mother Myth With Each Mom’s Story

- (Urban Moo Cow) His Perfect Mommy Is Just a Myth

Pingback: Dispelling Myths and Reinventing Motherhood » Mommy, For Real

Wowzers, Lauren. This is So. Good. Witty, funny, and spot-on. You are right that she is a chimera, changing for each of us and reflecting our deepest anxieties and fears. And I agree that it is getting better, more and more of us are telling our stories, but I think it’s still difficult. It’s like we can admit motherhood is hard, or that we question things, but if we ever admit we don’t like something of it, we get flamed. I think that part of the real mother, the ambivalence {kind of what I wrote about} is something we all feel but we really don’t like to talk about or admit to in public.

You’ve given me lots to think about…

What a great review, Lauren, and a spot-on analysis of the problem of this myth in the first place. (And interesting note that the backlash against probably won’t erase it try as we might.)

Another super blog.

Look forward to seeing a super daughter in April.

Love,

Dad

I love your characterization of the Good Mother as the shape-shifting boggart. How very, very true.

I’d love to talk more about the idea that the myth serves a purpose. I suspect you are on to something there, but I didn’t feel like you fleshed it out enough. Are you saying that we need the myth because it contains aspects of motherhood that are objectively desirable? That it serves as a necessary counterpoint to the equally pervasive myth of the “Bad Mother”? I feel we could talk for hours about this!

And hot damn, lady, you are an amazing writer. So much packed into each word here, I needed to read it twice!!

Yes, you are exactly right, I just let it sit there for the reader to take what she may. I suppose I mean three things:

1. With so many parenting choices and schools of thought out there, the Good Mother can help us pinpoint our stances on subjective questions, i.e. if we perceive her to be an attachment parent, who breastfeeds the kid until he is 2 and co-sleeps with him and baby-led weans him, then we can isolate those as goals for ourselves. Once we have those goals in mind, we can use her as an ideal-type and aim for them. If we fail to breastfeed for two years, and only make it to one, we might have gotten farther than we would have if we didn’t set our sight so high in the first place.

2. The nerves she strikes in us can help us to identify aspects of parenting we might want to do better. This is what I mean by saying she speaks different words to each of us. My version of the Good Mother is not the same as yours. The same FB posts won’t annoy us equally. If the Good Mother pisses us off because she has less/more kids or they all sleep well or she homeschools or whatever, we should reflect on why these particular things get under our skin. It is probably telling.

3. She does contain aspects that are objectively desirable. We all make mistakes and compromises and do things we aren’t particularly proud of. The baby rolls off the bed, we howl at the toddler because we are in a foul mood, we use too much muscle on the older kid, dragging him to his room. This reality doesn’t make us ‘bad’ mothers, but at the same time it’s not necessarily ‘good’ by anybody’s standards. Confessions from other moms who have done the same doesn’t mean we shouldn’t want to improve our own behavior.

I identify with #2 a lot. Sometimes asking yourself *why* things are upsetting you so much can help you figure out to stop them from getting under your skin.

I am also frustrated, generally, by the myth of the bad mother that you touch upon, like it’s something funny that we all wish we could be. Your #3 point is a more articulate and intelligent version of that.

Spot-on analysis, as usual! I loved how you incorporated the good mother myth manifesting as a “boggart”- that is such fascinating spin, and kind of perfect, actually! I also appreciated the idea of taking that myth and using it for our own good- whatever that may look like. Such an interesting angle, Lauren!

Love the idea you get at in the comments here, that what it is that irks us is probably telling. Agreed on the importance of real self reflection on these things-so much easier to be reactionary against others, or ourselves. Thoughtful piece.

I really like this post. I so like when people take time to question assumptions instead of just going along with them and clearly you did that here. I agree that if the “good mother” makes us feel bad it is because we let her and that if we look deeper we can see what it is we really want to do or be as parents.

And yet, for many parents (including myself when my kids were very young) it doesn’t feel like a choice. I felt so weighed down by guilt that I seemed to hear criticism everywhere. I guess that how we react to the “good mother” image is largely dependent on how much we value ourselves in the first place. I agree with you that others confessing to things we feel ashamed of doesn’t mean we shouldn’t strive to do things differently, but I also think that if it lifts some of the burden of shame then we will be more likely to respond differently in future anyway. The sad irony is that the more we punish ourselves for not being good enough mothers the more likely we are to repeat our errors. In my experience, letting go of guilt and learning to feel self compassion leads more easily to compassionate parenting than striving to become a better parent does.

Thank you for such a thoughtful comment, Yvonne, I really appreciate it and I take your point(s). I didn’t write this to play devil’s advocate per se, but I did want to delve deeper into the question of why, from an ideological point of view, the Good Mother persists so vehemently. So too I wanted to consider how, if she is bound to stay with us in her various incarnations, we can work with her and not against her. I am very interested in why some mothers are unaffected by her power and others succumb to it. I wonder if it is to do, as you say, with how much we value ourselves. Or, perhaps, with how much innate confidence we have in our ability to make choices and in the choices we ultimately do make. I think you are right that letting go of the guilt can lead to more compassionate parenting. I guess I wish we could aim to improve our own parenting framework *without* feeling guilty about the fact that we feel it needs improvement in the first place.

Your point that we can work with The Good Mother and not against her is such an important one. It makes total sense to do that. Fighting any internalised voice or image only gives us - a fight. You may already have come across Eleanor Longden, but if not: she’s a psychologist who healed from a diagnosis of schizophrenia by learning to work with the voices in her head instead of against them. In a way the Good Mother is a sort of split-off part of ourselves that we don’t see as us. When I felt that overall I wasn’t doing a great job as a parent, people would tell me I was doing it well and I didn’t believe them. It didn’t feel like me. I remember once playing with my kids and they were clearly having fun and the thought came to me, “This isn’t the real me. I’m not that nice.” Since then, I’ve heard many other people say the same sorts of thing. So we need accept the good in us as well as the bad.

And i also agree with you that the aim of improvement needs to come without feeling guilt that we need it! At some point in the past, someone pointed out to me that we can only ever do the best we can with the resources that we have at the time - and sometimes even if we have the cognitive knowledge that something is not best for our kids, we don’t have the emotional resources to act differently than we do. I find it very helpful to remember that, whilst also setting the intention to act with compassion.

By the way, I notice you are in Glasgow - I’m in Edinburgh so maybe at some time in the future we can have this discussion in “real life.” In any case, it’s very nice to have met you via the Brilliant book club!

That is all very well said. ‘We can only ever do the best we can with the resources that we have at the time – and sometimes even if we have the cognitive knowledge that something is not best for our kids, we don’t have the emotional resources to act differently than we do.’ Yes, a thousand times yes! And I think that phenomenon particularly applies to motherhood, where the emotions runs so high and our bodies and minds are taxed in a way and to a degree that is, quite frankly, startling.

I’ll check out the psychologist you mention, sounds like a fascinating story. And I’m excited that you are in Edinburgh. It’s nice to ‘meet’ someone local. I’ve found you on Twitter: I’ll look forward to keeping in touch (and reading your blog!).

I feel this idea you bring up is applicable beyond parenting. Whenever I feel like someone is telling me I’m not measuring up it’s because I internally believe that I’m not measuring up. It is easier to scorn ideals that I believe I can’t obtain than it is to try and maybe fail.

Alternatively the times I felt the least happy with my decisions were when I was trying to do things that were socially more acceptable, rather than doing what was really right for me, regardless of hard or easy.

I have to be true to my real desires, my personal ideals, and that starts with knowing what they are. I think when I’m really honest with myself I don’t get upset with others.

Great point, thank you! And I agree wholeheartedly. Sometimes we don’t dig deep, because we are afraid of what we will find. But, for me, really listening to that internal voice is often the best way forward. Societal standards can both help and hinder us in hearing it clearly. The trick, as you say, is knowing the difference.