Hilary Levey Friedman, the author of this month’s Brilliant Book Club pick Playing to Win, has a favorite gate. It is the one that gave her access to Harvard Yard and all such a yard entails. I walked through a similar gate in New Haven, Connecticut, but, unlike Levey Friedman, who says she wasn’t preened for an elite education, I was a carefully sculpted product of my mother’s ingenuity. I was raised with an emphasis on being ‘well-rounded,’ ‘a complete package,’ partly for its own sake but partly because this is how you got into an Ivy League university in 1995. When I was applying for college, my mother knew that academic achievement alone wasn’t enough to gain me entrance into the archway of my choice.

Like some of the kids Levey Friedman chronicles in her fascinating sociological study of America’s competitive youth culture - the subset she calls the ‘generalists’ - I participated in many after-school activities. Most of which I didn’t enjoy. I played the saxophone for a while, though I am essentially tone deaf. I was in Model Congress, where I wrote a Bill advocating for the conversion of abandoned missile silos into cryonic storage tanks (I’m not kidding). I know I did some community service or other because that was a box that needed to be ticked, but I can’t now recall, for the life of me, what it consisted of. My passion was for running, which I was good at (even if not university-level good) and it was this, once I was in high school, that came to take up the majority of my free time.

All of these activities, the loved and the merely tolerated, were well-documented on my college applications. Those sheafs of paper (they were still paper in my day) that shoot unadulterated panic into the hearts of teenagers and parents alike. I remember the process of filling them out, painstakingly, on my mother’s ‘Brother’ typewriter, the woodpecker-like tsk-ing of the correction tape working its magic on my myriad mistakes. In addition to the transcript of my grades and the laundry list of my extra-curriculars, there were the dreaded essays, the portrait pieces, which I typed out over and over again until they passed muster.

One of my essays was about being an anglophile. It was cute because I used British spelling: replacing the harsh American ‘z’ with the gentler hiss of an ‘s’ in words like ‘characterise’; partnering ‘o’ with the strangely superfluous ‘u’ in words like ‘harbour.’ I had spent the summer after my sophomore year of high school at Cambridge University - in a ‘Summer Discovery’ program(me) - and I knew I wanted to go back to this country of rain and crumpets and chronic apologies. What I didn’t know is that not only would I return for graduate school, first in London and then in Oxford, but I would ultimately settle and raise my own kids here.

My time at Oxford was illuminating in many ways, one of which was the exposure it gave me to the clockwork of another educational system. Let me tell you: there are serious differences between the way the Americans do it and the way the Brits do. I graduated from Yale with a degree in Classics, which was my ‘major,’ but also with the vaguer prestige of a ‘liberal arts’ experience. At Oxford, by contrast, undergraduates ‘read’ only one subject throughout their three-year stay. It is the classic dichotomy between depth and breadth, the hedgehog and the fox.

This call for early specialization is in part responsible for the very different nature of the admissions process in the UK and in the US. At Oxford, admissions is not centralized. There is a standard form (UCAS), the simplicity of which might bulge the eyes of an American parent. It includes some past exam grades, but for the most important exams (the A-levels) there appear only predicted grades, because these tests have yet to be taken. If you get called to interview, on the basis of this form, two or three of the tutors in the subject that you have applied to study, at the college-within-the-college you have applied to study it, will decide whether you get offered a place there. The only opportunity you have to mention any extra-curricular activity is in a single personal statement of roughly 650 words, where the guideline is to show ‘what makes you suitable’ for the course you are applying for.

My husband was a law tutor at Oxford for several years and he ran the undergraduate admissions at his college. The job of the admissions tutor, he says, is to assess intellectual ability and aptitude in regard to the particular subject of study. Unlike how Levey Friedman describes the kind of students Harvard is looking for, ‘ambitious individuals who are not afraid to take risks’ across a whole range of endeavors, what he was looking for was something much more pointed: the kid he wanted to be discussing the constitution with in an individualized tutorial at 9am on a Monday morning. This person, he says, very well might not be the student who was playing rugby or singing in the choir over the weekend. It is more likely to be the one staying in, diligently preparing his or her essay and poring over the law reports.

At Oxford, it is not that the interviewer doesn’t consider the candidate as the sum total of his or her experience. It is that the parts of that experience are not weighted separately, like melons at the marketplace, in quite the same way as they are in the US. As Levey Friedman makes the point: ‘That…colleges and universities consider admissions categories other than academic merit is…uniquely American.’

Top-tier education in Britain is about precisely that: education, narrowly construed. It is about mastery of a subject. Accordingly, versatility and a competitive edge are not the axes on which the admissions decision turns, as Levey Friedman characterizes the US system. The goal is not to admit a jack-of-all-trades. Nor is it to admit the future valedictorian. There is none. While somebody has to come top of the class at Harvard, this isn’t the case at Oxford. Any number of students can get a first class degree. You don’t need to edge anybody out to be the best.

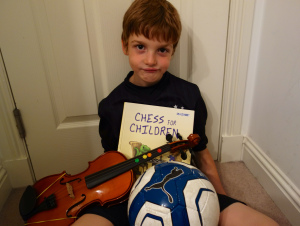

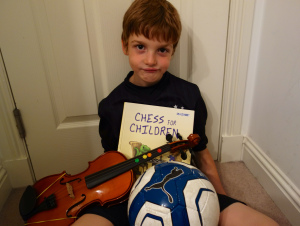

It’s just as well I live in Glasgow and not New York, where I grew up. We are one of the least scheduled families I know. My children do a lot of sports, but mainly in the backyard. The older one takes violin lessons, but these run during school hours. Their day is long enough as it is and, at eight and six years old, I don’t feel the need to lengthen it, for the sake of their career prospects or to stave off my own guilt.

I can’t tell if I under-schedule as a reaction to my own childhood or simply because it is my instinct and I feel safe following it in the knowledge that my kids won’t suffer as a result. They don’t ‘need’ a check-list of activities to get into a good university here and they certainly don’t need to be accruing such ‘credentials’ in primary school. Sure, people where I live might take their children to a couple of extra-curricular classes during the week. But nobody speaks of these things in the college-admissions-driven way Levey Friedman systematically outlines in Playing to Win.

When my kids come home at 4pm, they do their homework and then they play. Not to win, just to play. If they have a swimming lesson on the calendar one day, it isn’t so they get into Oxford in the future. It’s so they don’t drown.

See the other thought-provoking posts Playing to Win has inspired at the links below:

Like this:

Like Loading...